This story originally appeared in the March 2006 issue.

This story originally appeared in the March 2006 issue.

In late April of this year, California governor Jerry Brown submitted a proposal to address the issue that currently 729 California inmates have been sentenced to death, but San Quentin only has room enough for 690. His proposal requests about $3.2 million in order to build 97 more cells for these inmates on death row.

This isn’t the first time San Quentin has faced an overflow problem. In June of 2006, the California Department of Corrections was awarded $233 million to build 768 cells for death row inmates. However, since then the legislation has hit several roadblocks. By 2011, the estimated cost of the expansion project was $356 million. Due to budget cuts and the state deficit, Governor Brown decided to cancel the project.

Even as far back as 1972, California government was talking about closing San Quentin. Back then, operating San Quentin cost $9 million a year. Today, its annual operating budget is $164 million. And that’s without all the repairs and expansions that are desperately needed.

Today, the prison has almost become more notorious for its dilapidated facilities than its inmates, but not quite. Since its construction in 1852, criminals such as Black Bart, Richard Ramirez, Caryl Chessman, Sirhan Sirhan, Charles Manson, Scott Peterson, and the killers of Polly Klaas and Bill Cosby’s son have filled the cells. The prison has seen its fair share of celebrity visitors as well, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Joan Baez, Muhammad Ali, Whoopi Goldberg, Phyllis Diller, Johnny Cash, Woody Allen, Bonnie Raitt and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

It is not hard to imagine why this institution draws both celebrities and the public interest. Its origin story sounds like something from a movie. San Quentin was actually born on the water, aboard a 268-ton merchant vessel called Waban. This vessel housed 60 prisoners and was anchored off Point Quentin. Naturally, tempers got a little testy and space got a little cramped, so in 1852 the convicts built quarters that were then called Corte Madera Prison. Once the inmate population exceeded 500, however, the state took it over and renamed it San Quentin Prison.

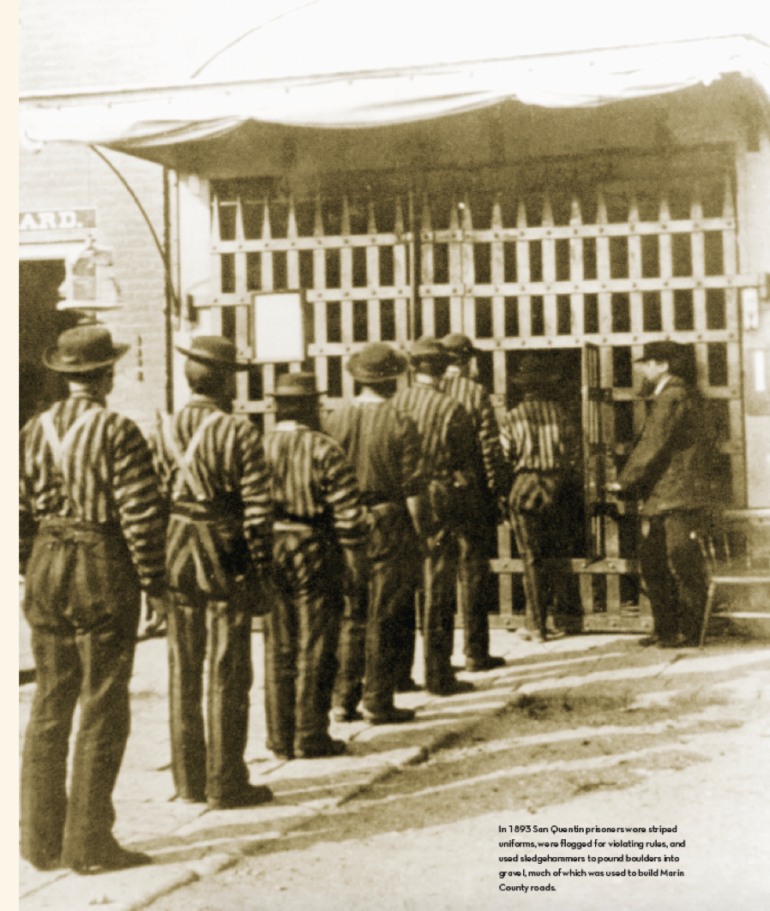

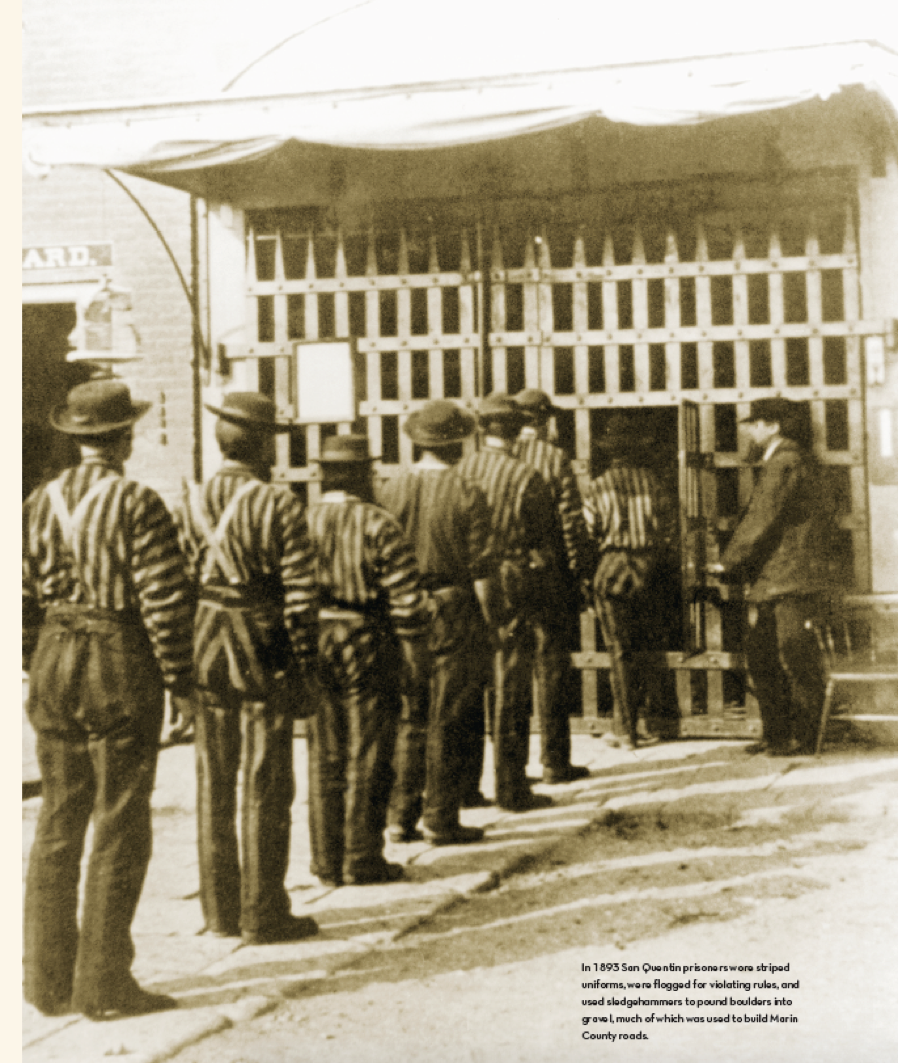

Instead of the infamous orange uniforms we associate with inmates today, the prisoners at San Quentin in the 1800s wore the more fashionable black-and-white striped uniforms. Also, it turns out they really did carry out their sentences by swinging heavy sledgehammers to break up boulders. Work which, interestingly enough, helped supply the gravel for many of Marin’s roads. Another remnant of the old San Quentin that has long disappeared is the method of execution; in those days, inmates on death row were hanged rather than lethally injected.

In 1913, San Quentin grew to include a 1,000-cell South Block, and by 1934, East, West and North blocks had been added. Needless to say, the San Quentin of 2015 looks very different from the San Quentin of 1852. Not only are there no longer any women, but inmates can now attend high school and college-level classes, as well as spend time in the library, snack shack, tennis courts and baseball field.

In 1937, San Quentin’s two-ton gas chamber was built. Before the ethical debate over the death penalty arose in 1967, six or seven inmates were executed each year. Since 1992, 13 executions have been carried out, including those of William Bonin, Stanley Tookie Williams, and Clarence Ray Allen.

With its crumbling architecture and overpopulation, San Quentin is certainly not the high security prison it once was. While Governor Brown and state legislators debate the cost-effectiveness of expansion and repairs, cells continue to fill and security continues to drop.

I’d say San Quentin is seeing more calamity than calm these days.