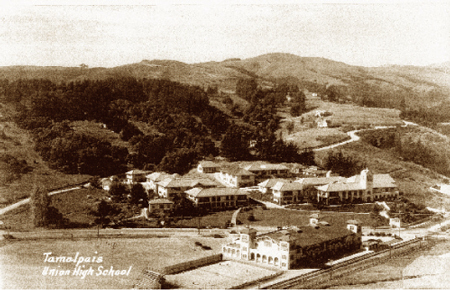

Most of us know the great San Francisco earthquake and fire occurred in 1906, but how many realize that two years later the first 70 students reported for classes at Mill Valley’s still-unfinished Tamalpais Union High School? Or that these two events were cause and effect? “In 1906, a major earthquake and fire destroyed a large portion of San Francisco and created a crowd of homeless refugees. Many sought shelter in Mill Valley, where there was only minor damage,” wrote Henri M. Boussy in the March 1998 issue of the Mill Valley Historical Society Review. “Construction of a high school had been contemplated since 1905. The new families added impetus to the demand and the procedure for establishing a public high school (in southern Marin) was initiated.”

Trustees worked with officials from the Northwestern Pacific Railroad before selecting the appropriate site. “On March 7, 1907, a campus on the proposed Mill Valley branch line was picked over a runner-up choice at Manzanita,” according to Barry Spitz’s Marin: A History. “Two parcels were purchased for a total of $3,309.”

Tamalpais Union High’s inaugural student body had 40 freshmen and 21 sophomores, but only five juniors and four seniors. (San Rafael High was already up and running, and not many older kids wanted to leave their classmates just for the sake of a shorter commute aboard the railroad’s “School Special.”) Original Principal Ernest Everett Wood, a congenial, meticulously dressed young educator, remained in that position for 36 years. According to historical accounts, he aimed for a “practical school that, in addition to cultural subjects, taught training for the world of business and manual labor.” His advice to students: “Play the game fair.”

Gene Stocking of Mill Valley, who graduated from Tam in 1941 and is still in touch with half a dozen classmates, recalls referring to Wood (behind his back, of course) as “Old E. E.” or “the Duke.” (That’s because “Mr. Wood, who also taught history, often referred to Miss Keyser, who taught English and drama and remained at Tam until 1947, as ‘the Duchess,’” she says.)

“I don’t have any bad memories of Tamalpais High. It was a wonderful school,” she says. “The grounds and gardens were so beautiful they were tourist attractions. Students were so proud we wouldn’t think of littering.”

One especially good memory: “I met my future husband there,” she says. “But he wasn’t a student. He drove the school bus.” With the railroad curtailing its operations in the ’40s as World War II approached, buses were being phased in, and young Bert Stocking became a driver while waiting to join the Army Air Corps. “I used to flirt with him in the rearview mirror,” Gene says. The couple married in 1945, had two children, both Tam High graduates, and now have four grandchildren, two of them also Tam alums.

T am High’s early years were infused with Wood’s philosophy of “learning through doing”; reportedly, his two most prized possessions were his carpenters union card and his Phi Beta Kappa key. Machine shop students built or helped build the tables and classroom music stands; the school stationery, yearbooks and newspaper were produced in the school print shop; and the home economics classes cooked and served cafeteria meals. By 1921 enrollment included kids from San Anselmo, Fairfax, Ross, Larkspur, Corte Madera, Tiburon and Belvedere. “You could hitchhike with the greatest of ease,” Bud Ortman told a newspaper reporter in 1998. “You’d put out your thumb and almost the first car would pick you up.”

am High’s early years were infused with Wood’s philosophy of “learning through doing”; reportedly, his two most prized possessions were his carpenters union card and his Phi Beta Kappa key. Machine shop students built or helped build the tables and classroom music stands; the school stationery, yearbooks and newspaper were produced in the school print shop; and the home economics classes cooked and served cafeteria meals. By 1921 enrollment included kids from San Anselmo, Fairfax, Ross, Larkspur, Corte Madera, Tiburon and Belvedere. “You could hitchhike with the greatest of ease,” Bud Ortman told a newspaper reporter in 1998. “You’d put out your thumb and almost the first car would pick you up.”

Wood and his family lived on campus for most of his tenure; he commemorated his four daughters’ births with the four towering redwoods that now dominate the school’s landscape. By 1927, the school had 15 departments offering 98 courses, 14 in music alone. Wood strove to make a “poor man’s college” out of Tam High—and in many ways, he did.

In 1937 during the Great Depression, teacher salaries were cut, volunteers coached athletic teams and the Works Progress Administration, aided by Tam wood shop students, built Meade Theater, still in use today (see “Tam High’s WPA Mural,” page 93). Still, through the 1930s and into the ’40s, Tam was recognized as one of the top high schools in California and, some say, in the nation. The school lost some students and top teachers with the opening of San Anselmo’s Drake High School in 1951 and Larkspur’s Redwood High in 1958.

In many ways Tamalpais High School has left its mark. Its illustrious alumni include Eunice Quedens, class of ’26, better known as Eve Arden, star of the ’50s sitcom Our Miss Brooks; Sam Chapman, ’34, a football All American at Cal and for years a Major League Baseball player; George C. Cory Jr., ’37, who wrote the music for the song “I Left My Heart in San Francisco”; Matt Hazeltine, ’51, an All American at Cal and later an All-Pro linebacker for the 49ers; Pat Paulsen, ’45, TV comedian and erstwhile presidential candidate; Tom Killion, ’71, noted woodblock artist; Kathleen Quinlan, ’72, actress in the films American Graffiti and Apollo 13; Joe Breeze, ’72, an inventor of the mountain bike; and Anne Killion, ’79, sports columnist for the San Jose Mercury News.

Image 2: Faculty at Tamalpais High School; E. E. Wood, principal, at far right (date unknown).

Tam High's WPA Mural

Restoration work needed on huge Depression-era artwork

It was the mid-1930s, FDR was in his second term and America was fitfully exiting the Great Depression. In Marin County, Maurice Del Mué , who had earlier designed the Arm & Hammer Baking Soda box and the Hills Brothers coffee can, could no longer find work as a commercial illustrator. So he took a job with the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Roosevelt-inspired program designed to get people back to work.

It was the mid-1930s, FDR was in his second term and America was fitfully exiting the Great Depression. In Marin County, Maurice Del Mué , who had earlier designed the Arm & Hammer Baking Soda box and the Hills Brothers coffee can, could no longer find work as a commercial illustrator. So he took a job with the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Roosevelt-inspired program designed to get people back to work.

Del Mué , who was born in Paris in 1875 but was then living in San Francisco, was working in a division of the WPA that did, of all things, artwork. In fact, he was a mural painter, one of several such artists who created an estimated 2,500 works of art in municipal buildings across America prior to the WPA being phased out in 1943.

“I believe Del Mué’s first Marin mural was for the Lagunitas School, which now is the San Geronimo Valley Community Center,” says Anne Rosenthal of Anne Rosenthal Fine Art Conservation of San Rafael, a prominent Bay Area restorer of artworks. That mural, which measures 6 feet by 26 feet, was painted in 1934, underwent a $14,000 restoration in 2004 and is available for viewing daily at the GVCC corner of Sir Francis Drake Boulevard and Meadow Way in San Geronimo.

Another of Del Mué’s WPA efforts, this one larger at 8 feet by 38 feet and titled The Golden Hills of Marin, was completed in 1938 and hung in Tamalpais High School’s assembly hall. “But in 1961 it was taken down, rolled up, and put in storage,” says Judith Wilson, a mother of two Tam alums, “and now there’s a fundraising drive under way to restore it and hang it in the school’s newly renovated library.”

Because The Golden Hills of Marin is so enormous and has been stored for so long, its restoration costs are significantly high. “Working with Anne Rosenthal,” says Wilson, “we estimate it could cost as much as $200,000 to have it restored and mounted.” Included in the cost is space for the yearlong restorative work to be completed. “So if anyone has an empty warehouse, they’d gain a nice tax credit by making it available,” says Wilson.

Further information on the “Tam’s WPA Art” fundraising effort is available at www.artfortam.org or by calling Judith Wilson at 415.435.0305.