“I CAN SEE YOU’RE EAGER TO MARK THAT FORM,” Adam says, taking a swift drag of his cigarette as he leads another volunteer and me down Bridgeway in Sausalito hours before dawn. “I know every single homeless person in this city; I could fill that whole thing out in three minutes.”

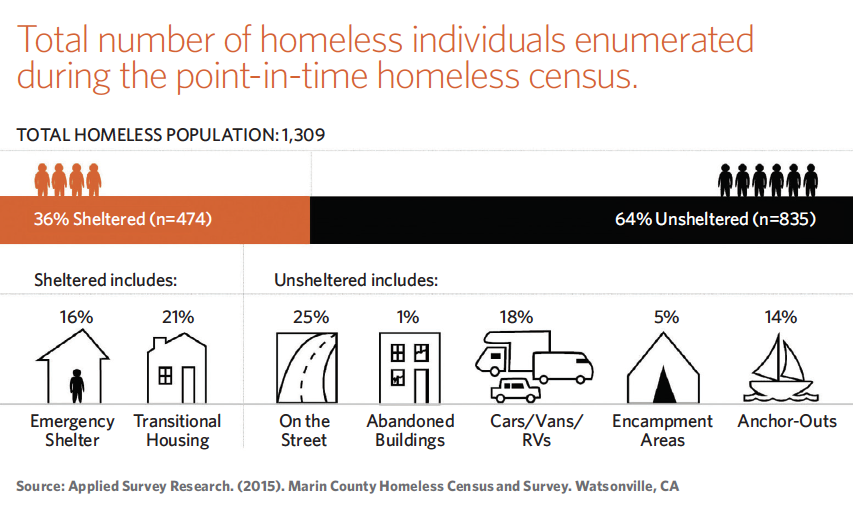

The form in question is part of the Point-in-Time Count (PIT), a biennial event that attempts to account for all the homeless individuals nationwide. Taking place during the last 10 days of January, the count is required of all counties receiving federal funding allocated toward homelessness by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Carried out by Applied Survey Research, a social research firm that conducts impact evaluations and assessments, the count focuses on individuals or families with primary nighttime residences that are not designed for or ordinarily used as regular sleeping accommodations for human beings. This criterion includes cars, parks, abandoned buildings, buses or train stations, airports, camping grounds and — something pretty unique to Marin — anchor-outs in Richardson Bay. After the tally, about 300 individuals, representing a broad spectrum of the population, complete an in-depth survey. When it comes to getting a snapshot of the current status of homelessness locally, this is the tool.

To help with the count, 15 volunteers gather at the Marin City Health and Wellness Center in Sausalito at 5 in the morning on January 27, carrying flashlights and wearing heavy jackets and athletic shoes. Similar groups of people also congregate in San Rafael and Novato. Before deployment — in order to get counters to the right spots — volunteers are paired up with guides who either currently are or have been homeless in the past.

Adam, whose house for the past three years has been an anchor-out in Richardson Bay, is one of the guides present the morning of the count. Late 30s with an average build, he wears a fleece-lined bomber hat and jacket, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle socks and Italian leather brown lace-ups. “I go through a pair of these a week,” he says, gesturing at the shoes. “The things people get rid of around here are unbelievable.” There are many reasons people end up without a home. For Adam, who holds a college degree, comes from a well-to-do family and has a Facebook account, untreated mental illness played a role. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 18, he self-medicated with alcohol for the next 20 years of his life. That led to multiple public intoxication arrests, and it wasn’t until a few years ago that rehab and proper treatment finally got him straight. “Now I just take a pill once a day,” he says. The county covers the cost of his medication.

As we walk past Dunphy Park, Adam recounts tales of other homeless Sausalito residents. One has been a dancer and did a stint in pornography before pursuing painting. Skeptical, I later research this story and, astonishingly, it checks out. Yet despite the variety of stories, the 2015 PIT survey revealed an undeniable fact about Marin’s homeless population — 71 percent were residents of the county prior to losing their housing, and 39 percent of that group had lived here more than 10 years. In such a wealthy county, how is it possible that so many moved from housing stability to instability? A look at the different stages of homelessness helps explain.

TRANSITIONALLY HOMELESS

People in this group make up 50 percent of Marin’s homeless population. These are people who have lost a job, had an unstable family situation, or got saddled with large hospital bills they were unable to pay, among other reasons. They generally go without a home anywhere between a month and a year. Robert* was recently utilizing the county’s Rotating Emergency Shelter Team (REST) program. Created to supplement the county’s shelter system, the REST program consists of about 40 local congregations that provide volunteers, meals, companionship and a place to sleep for up to 40 men and 20 women on a nightly basis when the weather is most severe — between November and April.

Robert shares his story over a REST dinner at St. Hilary’s Church in Tiburon. Already precariously housed, he was assaulted near the Canal Area of San Rafael, leaving his leg burned and him unable to work. While drug-free and mentally fit, Robert is divorced and his grown daughter lives out of state. Lacking a family support system, he has been relying on county services such as REST periodically until he gets well enough to work again.

EPISODICALLY HOMELESS

The second group comprises about 40 percent of the homeless population. Many of these people have been homeless for one to five years, though for some it has been far longer. Mental health issues and substance abuse often play a role, and while a lot of people in this group are functional and taking medication, they are struggling nonetheless.

With leading-man looks and a dazzling smile, Chase* also takes advantage of the REST program. After a tumultuous childhood that played out in his adult relationships, he eventually drank himself onto the streets: “I was involved in a toxic relationship that I didn’t realize was one when I became homeless,” he says, eyes downcast, muttering the final words. “I know what kind of people to avoid now and am seeing a counselor; they’re trying to set me up with a job.” While his progress looks promising, it still may not immediately get him off the streets — 28 percent of Marin’s homeless population is employed in some capacity, according to the 2015 PIT survey. Aside from getting a job, Chase wants to rent an apartment, which in Marin can be a challenge for even the well-adjusted: in 2016 the county had the fourth highest level of income inequality in California, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and median home prices were hovering around $1 million.

CHRONICALLY HOMELESS

The remaining 10 percent of Marin’s homeless population, its smallest contingent, is often the most problematic and visible — the chronically homeless. Largely the public face of homelessness locally, these are chronic inebriates who have been on the streets for many years, using alcohol, methamphetamines, crack, heroin or other hard drugs, often to deal with mental health problems like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Many don’t realize they have a problem. Describing some of the anchor-outs, Adam likens their situation to The Hunger Games, with rival factions that include a group of tweakers who steal from other anchor-outs. “It’s a rough life out there,” he says. “I get by, keeping to myself, but it’s not for everyone.”

PREVENTION AND DIVERSION

Prevention and shelter diversion assistance can reduce the size of the homeless population, by helping struggling households maintain a stable living situation. This approach has been successful in Sonoma and Santa Clara counties. Shelter diversion programs find people housing outside the shelter system, providing services to stabilize their situation or help them move into permanent housing. With half the county’s homeless population in the transitional stage, bolstering these kinds of efforts means fewer people entering the shelter system or seeking help with other basic needs. Organizations like Ritter Center, Adopt A Family and County of Marin Health and Human Services aid individuals in these situations.

MENTAL HEALTH CARE AND DRUG COUNSELING SERVICES

As of the 2015 PIT survey, there were 66 homeless veterans in Marin. Unfortunately, for a large number of them, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders did not recognize post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a legitimate illness until 1980, leaving symptoms untreated for years and vets to their own devices.

The reality is that approximately 1 in 5 adults in the United States — almost 44 million — suffer from mental illness in a given year. These are the reported numbers; they are likely higher. Destigmatizing mental health issues is integral to ending the problems that can lead to homelessness.

Operating under this principle, the County of Marin Health and Human Services, with its Meaningful Mental Health TV series, is aiming to increase public awareness on the subject and encouraging intervention before a crisis develops. Additionally, the city of San Rafael, which has the biggest homeless population in the county, created a Mental Health Resource Officer position in the police department to provide a specialized approach to those in need.

But you can’t talk about mental health issues and not discuss the role that drugs play. The war on drugs is widely seen as a loss, and an opioid epidemic is destroying communities across the country: when it comes to addiction, no one is immune. Instead of criminalizing addiction and funneling drug users to the streets and into prison, experts say, comprehensive rehab and recovery programs can get people the help they need. Providing drug-counseling and detox services outside of the emergency room can be a lot more cost effective: detoxing at a hospital in Marin comes to about $2,000 per day, or about 10 times the cost of care for a night at a detox center such as Helen Vine, the only nonmedical detox center in the county.

HOUSING FIRST

Salt Lake City, Utah, is often pointed to as the city that cured homelessness, getting 91 percent of people off the streets by providing them with housing. Utah discovered that like drug counseling, providing housing can actually save the public money.

Relying on emergency services is not cheap — the worst-off chronic inebriates cost Marin County $60,000 a year in emergency room visits, disturbance calls and use of other resources. Housing this same person would cost about half that and eliminate a lot of the stressful aspects of homelessness that exacerbate the existing conditions.

Of course, between Marin’s famed open spaces and NIMBYism, there is the issue of where to house individuals. “In order to enact large-scale change there needs to be cooperation on an executive level,” says San Rafael’s first-ever director of homeless planning and outreach hired last year, Andrew Hening. “This includes partnerships between county services and businesses.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. What works for Utah may not work for Marin. Business owners and residents’ feelings on the issue run the gamut; many are both frustrated and concerned about the people lying on the street. Results from this year’s count will be available in May and should give a clearer picture of the current situation. But looking further out, what can be done to fix an ineffective system that’s allowing homelessness to happen?

The federal appointment of Ben Carson to head HUD and the planned dismantling of the Affordable Care Act has many experts in the field worried. But Hening thinks much can be accomplished at the local level before the situation get truly dire: “Oftentimes in life, it’s a crisis that mobilizes us into action.”

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.

Local Resources

These are just some of the many organizations helping to put an end to homelessness throughout the county. If you know someone in need of behavioral, recovery or social services, direct them to Marin Health and Human Services.

Adopt A Family of Marin

Adopt A Family prevents homelessness and provides stability for families in crisis with subsidies for rental assistance, security deposits, utility payments, food vouchers and auto repair.

Buckelew Programs

Buckelew Programs include Marin’s only nonmedical detox center, Helen Vine, and Family Service Agency of Marin, which provides accessible mental health services to children, adults and families.

Homeward Bound of Marin

Homeward Bound of Marin is the county’s primary provider of shelters and services for homeless families and individuals.

Ritter Center

Each year Ritter Center assists more than 4,000 low-income and no-income individuals and families who are without a home or at risk of becoming homeless in Marin.

St. Vincent de Paul Society

The Saint Vincent de Paul Society of Marin provides essential services to meet the needs of the local homeless and working poor, including food, housing, crisis assistance and the REST program.

Sunny Hills Services

The mission of Sunny Hills Services is to help vulnerable children, youth and their families use their strengths to develop healthy relationships and fulfilling lives.

Warm Wishes

Warm Wishes distributes backpacks stuffed with warm gloves, scarves, hats, wool socks and rain ponchos to homeless men, women and children living on the streets.

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s print edition under the headline: “Falling Through the Cracks.“

Kasia Pawlowska loves words. A native of Poland, Kasia moved to the States when she was seven. The San Francisco State University creative writing graduate went on to write for publications like the San Francisco Bay Guardian and KQED Arts among others prior to joining the Marin Magazine staff. Topics Kasia has covered include travel, trends, mushroom hunting, an award-winning series on social media addiction and loads of other random things. When she’s not busy blogging or researching and writing articles, she’s either at home writing postcards and reading or going to shows. Recently, Kasia has been trying to branch out and diversify, ie: use different emojis. Her quest for the perfect chip is never-ending.