My climb to the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro was like childbirth—more difficult and more rewarding than I ever imagined. It required more concentration, stamina and strength than I thought I possessed. I saw no choice but to push through the pain and keep climbing, though in those moments I questioned why I was doing this in the first place.

My husband, Steve, and I had been to Africa 12 years before, traveling for six weeks in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and South Africa to make a video on eco-lodges. This time, we were off to Tanzania, producing a video for Roadmonkey Adventure Philanthropy.

Started by former New York Times journalist Paul von Zielbauer, Roadmonkey trips combine rugged adventure travel with meaningful volunteer work. Since its inception in 2008, Roadmonkey has led three expeditions and raised more than $30,000 for worthy causes. On this trip, we would first climb to the 19,340-foot summit of Kilimanjaro in Tanzania and then complete a volunteer project for Bibi Jann School, a nonprofit organization for children orphaned by East Africa’s AIDS epidemic.

Eight of the 10 people in our group were women, among them a graphic artist, a financial analyst, a school administrator and a representative from the U.N. There was a 21-year-old student from Denver (nicknamed “Free Spirit”) and a 42-year-old Detroit mom of three (“Mother”).

Despite our differences, we had each chosen to travel across the world in search of an adventure that would stretch our limits physically, intellectually and culturally.

The Road to Kilimanjaro

The launching point for our seven-day Kilimanjaro trek was Moshi, a town on the lower slopes of the mountain. We left early on a Sunday and drove several hours through tiny rural townships where simple mud huts stood in stark contrast beside shops displaying bright blue billboards for Vodacom, the local cellular provider. We passed fields of corn, carrots and sunflowers. Chickens scratched amid the dust, dirt and roadside trash. Villagers of all ages carried buckets of water or enormous bundles of wood atop their heads. Brightly dressed women, some with babies strapped to their backs, tended open fires and children ran barefoot toward our bus to see the mzungus (Swahili for white people).

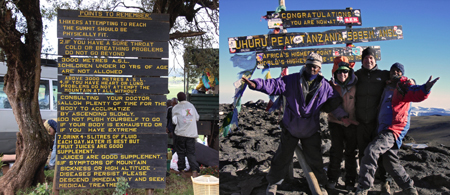

At the ranger check-in station for Kilimanjaro National Park, a huge sign listed health precautions and recommendations. Anyone showing symptoms of acute altitude sickness (dizziness, nausea, vomiting) must descend immediately and seek medical attention, it cautioned. I’d read the warnings sent by our guide company, Tanzania Journeys, yet seeing them repeated in bold on a 50-by-50-foot sign made it feel more menacing.

We were in good hands, though. Our guide was only 31, but he possessed an air of quiet wisdom gained in more than 20 years of experience on Kilimanjaro. His name was Good Luck Charles and we joked that we were glad to have good luck on our side.

The road to the trailhead was washed out by heavy rains, but our beat-up Land Cruiser delivered on its off-road promise, navigating through deep muddy ruts and exposed tree roots. Finally, we were ready to hike. For the next week, we followed the Lemosho Route, one of the longest and most remote trails to the summit. But it ascended gradually and gave our bodies time to acclimatize as we passed through the diverse ecological zones of Kilimanjaro.

The road to the trailhead was washed out by heavy rains, but our beat-up Land Cruiser delivered on its off-road promise, navigating through deep muddy ruts and exposed tree roots. Finally, we were ready to hike. For the next week, we followed the Lemosho Route, one of the longest and most remote trails to the summit. But it ascended gradually and gave our bodies time to acclimatize as we passed through the diverse ecological zones of Kilimanjaro.

Day one began with a steady climb through dense rain forest. At places, the ground crawled with a living carpet of huge fire ants. “Careful, step over,” Good Luck cautioned. We were more than happy to oblige, recalling those movie scenes in which some poor soul is devoured by swarms of angry ants and carried away screaming.

We saw black-and-white colobus monkeys swing in the upper branches of trees and came upon large mounds of fresh elephant dung, although the majestic creatures eluded us. Thick gray moss draped the trees and the air was dense, warm and moist. Before long, we peeled off layers and glistened with sweat. Under the shade of a large tree, we gobbled up a simple sack lunch.

As we rested, our porters passed, carrying our backpacks and camping gear, 40 to 50 pounds apiece. While we struggled not to trip over roots or founder in the mud, these men glided over the terrain, sacks of gear balanced on their heads. They aptly called themselves Wagumu (hard core) and they earned our awe and respect. They also brought us our first Swahili lesson:

Mambo vipi? – “How’s it going?”

Poa! – “Cool!”

Four hours of hiking brought us to our first campsite, where our tents sat under a thick canopy of trees. We donned headlamps and met for dinner at the mess tent. Togolai, our shy waiter, welcomed us with fresh water for hand washing. Inside, we balanced on tiny triangular camp chairs to savor warm cucumber soup, bread and chicken vegetable stew.

Meal times were a treasure. We laughed at each other and ourselves, sharing travails of the day. All of us were outside of our comfort zones and found solace in the bond of the group.

The Lesson of Pole’ Pole’

The next day we left the rain forest and crossed into the giant heather “moorland,” where there was little shade to protect us from the full strength of the African sun. After only two hours of steep climbing, we tired. Good Luck encouraged us onward. “Pole’ pole’,” he’d say, meaning slowly. Pole’ pole’ is Kilimanjaro’s essential lesson and it became our mantra.

At midday we reached a small cliffside plateau. The porters, who carried four times as much as us and walked twice as fast, had set a lovely lunch table. Enjoying the roasted chicken, boiled eggs and oranges, I looked to the view and to the faces of my new friends and felt a profound sense of gratitude. That afternoon, as we crossed spectacular valleys and streams, the heat was relentless and exhaustion set in. Camp was “just over the next ridge,” our guides said, but that ridge never seemed to arrive. Eight hours passed. I ran out of water and fell far behind the group. Regular hikes in the hills around my Muir Beach home had not prepared me for this. Simon, a muscular guide with a serious demeanor, kept me going, “Just a bit further, pole’ pole’.” This would not be the last time that Simon would get me through.

The destination that evening was Shira Ridge (12,628 feet), which rewarded us with 360-degree views and the sight of Mount Meru, an extinct volcano, off in the distance. Night was clear and cold. The sky sparkled with more stars than I had ever seen. In the morning, thick clouds, seemingly thousands of feet below, extended to the horizon. I felt like Athena on Mount Olympus, living among the clouds turning pink, as the sun came up.

Over the next few days, we ascended through semi-desert, then alpine desert, and scaled boulders up the Great Barranco Wall. We gained stamina and confidence conquering each day’s challenge. At times we chatted and laughed, or practiced our Swahili with the guides. When we struggled, we quieted and focused, pole’ pole’.

Over the next few days, we ascended through semi-desert, then alpine desert, and scaled boulders up the Great Barranco Wall. We gained stamina and confidence conquering each day’s challenge. At times we chatted and laughed, or practiced our Swahili with the guides. When we struggled, we quieted and focused, pole’ pole’.

As we moved higher, Good Luck became our watchful father, monitoring our health and offering solutions. At day’s end, our porters welcomed us with spirited singing and clapping. We approached the final campsite at 15,000-foot Barafu Hut under light snowfall and slept on an exposed ridge. At midnight we woke, donned headlamps, layered up with warm clothing and began the last leg to the summit—a brutal, eight-hour slog up steep rocky terrain. No one spoke. We labored one tiny step at a time. I saw hundreds of tiny headlamps ascending thousands of feet above me. The sight was so discouraging I concentrated on the two feet directly in front of me.

The extreme cold and lack of oxygen took its toll. I nodded, narcoleptic-like, into nanoseconds of sleep. Then I’d snap my eyes wide open, shake it off and say to myself, “wake up!”—all the while walking, walking, walking.

My husband stayed close, providing encouragement—“only two more hours and the sun will be up.” Simon offered to carry my pack. Another guide, Job, walked in front, setting a slow, rhythmic pace and serenading me with soothing song in Swahili.

When sunrise came, the sky glowed blood red and the astounding beauty refreshed me. At Stella Point just below the summit, I saw the famed glaciers pulsing iridescent blue. During the last few hundred steps to Uhuru Peak, I looked intently at my surroundings, wanting to forever imprint my time on the rooftop of Africa.

As our group reached the summit one by one, we hugged, cried and celebrated. Good Luck beamed and cheered, “Congratulations! You have conquered the mountain!”

Climbing Higher

After such an exhilarating week, we couldn’t imagine an experience to top it, but we headed to Dar es Salaam for the volunteer portion of our adventure.

Dar es Salaam is the largest city in Tanzania and the de facto capital. Its bustling center feels like a circus on steroids. Street vendors hawk everything from sugarcane to cell phones. Driving is chaotic, with cars, trucks, buses, pushcarts, pedestrians and an occasional goat all vying for space.

We traveled in a green-and-purple bus we fondly named the Mystery Bus, partly because of its resemblance to the bus from Scooby Doo and partly because we were never sure when it would arrive. The bus came with a driver and two additional men, who were there for our protection. Dar es Salaam can be dangerous for white tourists and the biggest guy positioned himself in front of the doors as we rode on the crowded streets, making sure no “unintentional” passengers hopped on board.

The Bibi Jann Children’s Care Center and School is located in Mbagala, a small village on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam. The school was started in 2001 by Fatuma Gwao, a retired teacher who wanted to help some of Tanzania’s almost 1 million AIDS orphans. What started as a one-room preschool has grown to become Bibi Jann Children’s Care Trust, which oversees 130 students, teaches adult literacy, and supports grandmothers (bibis) who care for their orphaned grandchildren with a Bibi-2-Bibi program.

The Bibi Jann Children’s Care Center and School is located in Mbagala, a small village on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam. The school was started in 2001 by Fatuma Gwao, a retired teacher who wanted to help some of Tanzania’s almost 1 million AIDS orphans. What started as a one-room preschool has grown to become Bibi Jann Children’s Care Trust, which oversees 130 students, teaches adult literacy, and supports grandmothers (bibis) who care for their orphaned grandchildren with a Bibi-2-Bibi program.

At first glance, the school appeared bleak and colorless. Rusty, worn and what looked to be mostly broken playground equipment filled a dirt courtyard, along with a forlorn stucco giraffe. “Wow”, I thought, “this is so sad.”

Inside, the children had prepared a welcome for us. A group, probably second- or third-graders, stepped to the front of the classroom. A girl and boy began to sing. Their voices were so pure and clear that tears came unexpectedly to my eyes.

Maybe I simply missed my own young son, Ryan, so many miles away, or maybe the purpose of our visit crystallized at that moment. Soon, all the kids were singing and clapping and stomping, acting out a complex set of tribal dances to the intricate rhythms of a small drum.

After the show, the kids rushed out to that rickety playground and I saw how wrong my first impression had been. They were having a blast, spinning with abandon on the rotating “whirlybird” and sliding down the wood plank slide. The giggles and squeals of delight assured me that there was nothing sad about the Bibi Jann School.

A tiny hand grasped mine. I looked down to see a girl of about 4 grinning up at me. We considered each other for a moment and then, seeing that I was nice, a dozen more children crowded around. They held my hand and touched my skin. They stared at my Western clothing and searched my face. I showed them a photo of my son and the children took turns holding the picture. They looked from the photo to me and back. We did the Swahili version of high five, going to knuckle to knuckle to exclaim “nepitano!” Just like that, we were friends.

Digging In

We divided into groups and started our projects—install a filtration system for clean drinking water, put in a new gas stove, build 30 desks, and paint and decorate five classrooms. Roadmonkey volunteers work side by side with locals. George, an energetic young kindergarten teacher, directed our classroom project. After two days of prepping, priming and painting, we got to the glory work of adding numbers, letters and drawings to decorate the walls. One elderly villager wandered in and gave us his opinion, which George translated: “He says the bus is no good—you need to draw it better.” Even in this remote corner of the world, you can’t escape a critic.

The days at the school were hot, dusty and tiring. Each day, Fatuma welcomed us into her home for a traditional meal of rice, beans and vegetables. Sometimes, they added fish broth or avocado or fresh oranges, always sharing the best of whatever she had. We recognized this as a special opportunity that most tourists never experience.

On the last day, the children filed in and sat at the desks we’d made. The headmaster quizzed them on their letters and we beamed with delight as they recognized our hand-painted drawings of fruits, vegetables and yes, even the bus. We left feeling satisfied that we’d left “our school” a bit better for our efforts. The children had new desks and bright classrooms, the bibis had a new stove and everyone had clean drinking water. As we pulled away in the Mystery Bus, the children ran after us, smiling and waving goodbye, an image that will stay with me forever.

From the tallest mountain to the tiniest hand, Tanzania had bestowed its many gifts on us—the bright eyes of children so eager to learn; the bibis so warm and caring; the songs of the porters on the mountain; the bond among us as we struggled and achieved; and, of course, the wisdom of pole’ pole’ that had served us so well.

Bayside Entertainment’s Steve Wynn created video footage of his and Joanie’s Tanzania travel experience. To view, click here.