FIFTY YEARS AFTER San Francisco’s Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury district became a symbol for the burgeoning hippie movement, several museums will highlight counterculture design and its modern-day impact.

FIFTY YEARS AFTER San Francisco’s Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury district became a symbol for the burgeoning hippie movement, several museums will highlight counterculture design and its modern-day impact.

Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, organized by the Walker Art Center and curated by Andrew Blauvelt, director of Cranbrook Art Museum, with the assistance of the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, will be the first such exhibition to open in the Bay Area, February 8–May 21 at BAMPFA.

The museum’s director, Lawrence Rinder, and UC Berkeley associate professor of architecture Greg Castillo have added works by Bay Area artists such as sculptor/builder J. B. Blunk and designer Frances Butler, as well as vintage ephemera, photographs and films, to highlight the transformation launched by 100,000 young antiwar rebels who gathered for a human be-in at Golden Gate Park and changed the course of the ’60s and ’70s.

“Hippie Modernism is the deliberate collision of two terms that provoke a conceptual conflict,” Castillo explains. It recasts much-maligned “smelly” hippies as having the disruptive qualities that modern technology firms cherish. “The term hippie was a media invention that typically defined the counterculture by its lowest common denominator. We often remember sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, but not the aesthetic experimentation that went with them,” Castillo says.

“Hippie Modernism is the deliberate collision of two terms that provoke a conceptual conflict,” Castillo explains. It recasts much-maligned “smelly” hippies as having the disruptive qualities that modern technology firms cherish. “The term hippie was a media invention that typically defined the counterculture by its lowest common denominator. We often remember sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, but not the aesthetic experimentation that went with them,” Castillo says.

But the alternative communities in cities like San Francisco and in rural Sonoma and Humboldt counties, where land was cheap, became in essence startup enterprises — generating funds for a community short on cash yet rich in skills and innovation. Counterculture members were the first to raise consciousness about sustainable living, regenerative design that mimics nature, social justice and the virtues of shared economies, concepts that have now become mainstream.

But the alternative communities in cities like San Francisco and in rural Sonoma and Humboldt counties, where land was cheap, became in essence startup enterprises — generating funds for a community short on cash yet rich in skills and innovation. Counterculture members were the first to raise consciousness about sustainable living, regenerative design that mimics nature, social justice and the virtues of shared economies, concepts that have now become mainstream.

In Berkeley, for instance, hippies invented methods of linking industrial waste to consumer practice and began recycling. They introduced a DIY building movement, in which artists such as Butler printed fabrics and made clothes she described as “reading environments.” In the San Francisco psychedelic free theater group Angels of Light, bearded gay men in drag viewed their bodies as laboratories of cultural evolution. Such new zones of enterprise, which architect Buckminster Fuller might have called “liberated territories,” Castillo says, also included, in Santa Cruz, organic farming, which has mushroomed into a more than $43 billion industry nationwide.

The exhibition juxtaposes Community Memory, a 1973 public computer network formed in Berkeley by members of the Village of Arts and Ideas commune, with today’s online social communities like Twitter to show how the Bay Area’s counterculture foreshadowed the World Wide Web. “Open source and open spirit led to the very structure of the internet,” Rinder says.

The exhibition juxtaposes Community Memory, a 1973 public computer network formed in Berkeley by members of the Village of Arts and Ideas commune, with today’s online social communities like Twitter to show how the Bay Area’s counterculture foreshadowed the World Wide Web. “Open source and open spirit led to the very structure of the internet,” Rinder says.

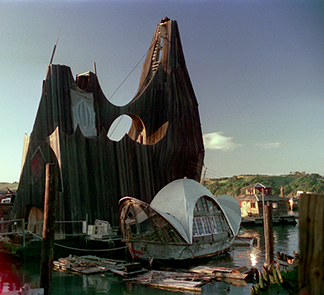

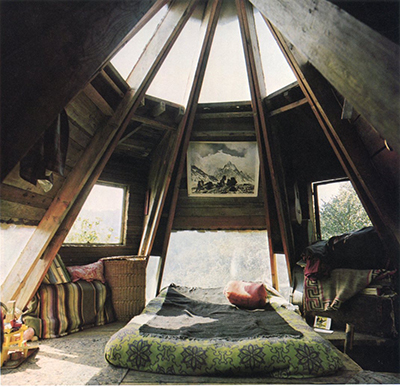

“Hippies were self-building in every way,” Castillo observes. “They created homes that could not be understood within establishment conventions of modern design and that were torn down because building inspectors targeted their ragtag communities.” One of the most successful anarchist communities living on Sausalito houseboats was systematically destroyed but its impact spread as hippie modernism produced a new cultural geography. Its nomads moved between New Mexico and the Bay Area, which had each become epicenters of unconventional lifestyles and related publishing. The underground publication San Francisco Oracle reached nearly 500,000 readers at its height. In Mendocino County, the Albion Nation, a back-to-the-land retreat, published an influential feminist journal called Country Women.

“The surge of counterculture publishing served as a teaching tool and an open resource like the Whole Earth Catalog,” Castillo says of the back-to-the-land handbook published regularly from 1968 to 1972.

“The surge of counterculture publishing served as a teaching tool and an open resource like the Whole Earth Catalog,” Castillo says of the back-to-the-land handbook published regularly from 1968 to 1972.

The ideas were disseminated and spread to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to upstate New York and along the international hippie trail from London to Goa, India, and on to Sydney, Australia. “Cheap printing, underground newspapers and posted flyers were the hippie internet,” Castillo says. “They were social media for pilgrims in search of self and new communities marked by evolutionary consciousness.”

70’s Legacy

70’s Legacy

Four artists’ and writers’ dwellings designed in 2011 by San Francisco– and New York–based architect Cass Calder Smith, who grew up in a Santa Cruz Mountains off-grid commune in California during the ’70s, are the size of shipping containers, all aimed at ocean views. They are for participants in the lauded Djerassi Resident Artists Program, founded in 1979 by chemist Carl Djerassi on a former cattle ranch in coastal Woodside in the Peninsula. The modern studios by CCS Architecture (not included in Hippie Modernism) echo hippie design-build structures on the West Coast. A canted steel frame canopy with solar panels and skylights hovers, above these communal yet private live/work wood-clad pods, like a stretched tarp. Interestingly, Djerassi was also one of the creators of the 1960s contraceptive pill that became a catalyst of the sexual revolution during the hippie era. The relatively new studios are dedicated to his wife, feminist writer and Anne Sexton biographer Diane Middlebrook. djerassi.org

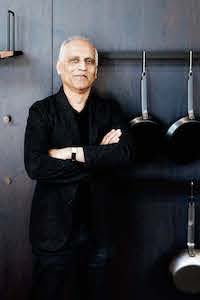

Zahid Sardar brings an extensive range of design interests and keen knowledge of Bay Area design culture to SPACES magazine. He is a San Francisco editor, curator and author specializing in global architecture, interiors, landscape and industrial design. His work has appeared in numerous design publications as well as the San Francisco Chronicle for which he served as an influential design editor for 22 years. Sardar serves on the San Francisco Decorator Showcase design advisory board.