(Top) In the living room, dominated by a black steel sculpture by Brian Wall and Manuel Neri’s marble 1989 Odalisque 1 on the floor, are a Louise Nevelson–esque bookshelf and steel pivot door to the kitchen that Francis Mill designed with Chris French. Visible on the kitchen wall is Neri’s 1960 red plaster-and-cardboard Moon Sculpture II. On the ceiling above the Eames chair is Emerson Woelffer’s 1954 oil on canvas Colorado. Near the daybed/banquette by interior designer Stephan Jones is a portrait by David Park.

(Below) The daybed directly under Sentinel, a 1961 collage by artist Conrad Marca-Relli, doubles as Mill’s guest bed. The wood shutter flanking the front door on the right screens out lights in the hallway outside at night. A minimalist coffee table designed by Mill and French is made of salvaged lumber fitted with steel legs. In the foreground, left, a sculpture incorporating a weighing scale is by Mill; he is seen standing, in the vignette on the right, near a scroll painting by his father.

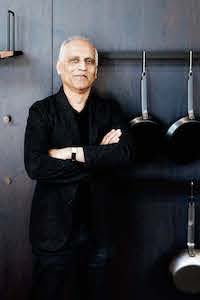

RECENTLY, AT FRANCIS MILL’S home in a former 1937 warehouse in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood, the usually effusive gallerist seemed subdued. The British painter Howard Hodgkin had died just the day before.

Mill’s San Francisco gallery, Hackett Mill, represents the work of midcentury abstract expressionists like Hodgkin, and a couple of his paintings hang inside Mill’s home. “They will be moved often,” Mill says, “to form new ‘conversations.’ When artists are gone, you can talk to them in this way.”

The 1,300-square-foot one-bedroom loft, remodeled during the 1980s, had Pompeiian red walls, heavy drapes and wrought iron details when Mill acquired it in 2005. That’s gone now.

The board-formed concrete walls, troweled ceilings and scored floors are again a brutalist gray and the drywall partitions white, forming a neutral container for art.

The front door opens into an L-shaped living/dining room. Next to it, a room with west-facing windows, previously the building’s elevator shaft, was turned into an art studio and home office. Flanking these spaces are the kitchen on the northeast corner and the northwest-side bedroom, linked by a 3-foot-wide hallway running parallel to built-in closets and a bathroom sandwiched between both rooms.

The front door opens into an L-shaped living/dining room. Next to it, a room with west-facing windows, previously the building’s elevator shaft, was turned into an art studio and home office. Flanking these spaces are the kitchen on the northeast corner and the northwest-side bedroom, linked by a 3-foot-wide hallway running parallel to built-in closets and a bathroom sandwiched between both rooms.

Mill, who studied architecture and fine arts before becoming the dean of graduate studies at the Academy of Art University, treats the interior like an assemblage sculpture, creating unexpected juxtapositions of art and modernist furnishings.

“My process is spontaneous. Sometimes when I look up from a book I am reading, I get an idea,” Mill says. That’s how he thought of suspending an Emerson Woelffer canvas from the ceiling above an Eames chair his mother gave him.

In 2007 Mill recruited Oakland metalsmith Chris French to replace an entertainment unit between the living room and the kitchen hallway with new bookshelves. During demolition they realized that with the unit gone, they had better access and sight lines from the living room into the kitchen. So they kept the opening and fitted it with a floor-to-ceiling pivot door of black steel panels riveted together, as a nod to sculptor Louise Nevelson. Next to it, a portal to the original hallway was filled in with Nevelson- esque black painted stacked wood and steel crates for Mill’s art books.

Craving more storage and display areas, Mill identified unused pockets of space in soffits, around columns and in corners, and in 2013 he asked Los Angeles interior designer Stephan Jones to help him maximize every square inch.

Jones, who also happens to be a collage artist, is Mill’s perfect foil. They are friends and met professionally when Jones and his art-buying clients first visited Mill’s gallery more than 10 years ago.

“We always discuss concepts and aesthetics easily,” Jones says.

Together he and Mill made the loft into a truly versatile space. They ripped out closets, kitchen cabinets and unwanted doors to free up walls, and they introduced custom millwork from Henrybuilt.

With fewer doors, “it is a sequence of semi-enclosed spaces,” Jones says. “There is always a sense of something beyond what’s visible.”

The new storage is more efficient and makes the place, as Mill says, quoting the architect Le Corbusier, “a machine for living in.”

For example, in the bedroom where there is just a bed and chair because “we abolished unnecessary furniture,” Mill says, the closet now has a hinged, boxlike raw plywood “door” inspired by Donald Judd’s sculpture. The closet is a “dressing” container with a full-length mirror, shoes and other accessories that you can walk into when the door is opened.

Storage cupboards in the hallway have flat panel doors that double as walls to hang art on. One cupboard has built-in drawers finished with blackboard paint so Mill can leave laundry instructions for the maid; sliding drawer lids are for folding shirts on; very shallow shelves behind the cupboard door neatly hold Mill’s vast collection of eyewear.

For the art studio, Jones and Mill designed a long desk with storage drawers — including one filled with sand for a miniature indoor Zen garden — and flat file drawers with compartments for art supplies, wood blocks and other materials for sculpture. On the north wall, new bookshelves by French are fitted with a vertical steel blackboard for writing notes; it rolls from side to side on a track.

For the art studio, Jones and Mill designed a long desk with storage drawers — including one filled with sand for a miniature indoor Zen garden — and flat file drawers with compartments for art supplies, wood blocks and other materials for sculpture. On the north wall, new bookshelves by French are fitted with a vertical steel blackboard for writing notes; it rolls from side to side on a track.

A banquette and bookshelves form a dining alcove in the living area. Another space-saving feature — a daybed divan with storage underneath, tucked into a niche by the pivot door — doubles as a guest bed.

The center of the open-plan room is currently taken by a solid life-size marble torso by Manuel Neri, reclining on the floor beside a black 10-foot-high constructivist welded-steel work by Emeryville-based British sculptor Brian Wall. Near it, a white painted 10-foot high wood totem by ’60s sculptor Richard Faralla also seems permanent and immovable.

However, “the core elements of Brian’s sculpture are not solid. The form is merely outlined in steel and is quite light,” Mill says, adding confidently that even if it were heavy, he could move it. He’s had practice. Mill’s family used to have an appliances and furniture business in the Mission District, where he sometimes handled large crates.

Now as a purveyor of art he reveals a deeper family bond: his father, who emigrated from Hong Kong, is also a painter, and one of his minimalist brush renderings on a rice paper scroll hangs near Wall’s sculpture.

The senior Mill’s calligraphic meditations often describe a mood or thought, perhaps referencing the flight of birds or reflections of bamboo in a pool of water, but “their essential message, that there is great complexity within simplicity, has many parallels in Western painting,” Mill notes. “Consider Rothko or Agnes Martin. The main reason we feel that Western and Eastern art do not have similar messages is that they look so different.

“It was just this kind of cross-cultural dialogue that can be described as an American vision that led to abstract expressionism,” he adds. “In New York, Kenzo Okada was shown alongside de Kooning and Pollock.”

Clearly, for a collector, buying art is just the beginning. “Living with it is an ongoing conversation,” Mill says. “I can never get enough of that.”

Zahid Sardar brings an extensive range of design interests and keen knowledge of Bay Area design culture to SPACES magazine. He is a San Francisco editor, curator and author specializing in global architecture, interiors, landscape and industrial design. His work has appeared in numerous design publications as well as the San Francisco Chronicle for which he served as an influential design editor for 22 years. Sardar serves on the San Francisco Decorator Showcase design advisory board.