HILLS AND TREES to climb and ponds to swim in are missing in rigidly planned and aging postwar city parks. This fact has had a constraining effect on children’s play and their ability to socialize with other children for half a century. Slides in such parks are like stiff funnels, and swings move only in prescribed arcs, leaving little room for imaginative interaction.

HILLS AND TREES to climb and ponds to swim in are missing in rigidly planned and aging postwar city parks. This fact has had a constraining effect on children’s play and their ability to socialize with other children for half a century. Slides in such parks are like stiff funnels, and swings move only in prescribed arcs, leaving little room for imaginative interaction.

But such limiting ideas for play spaces have begun to fade, thanks to the decades-long efforts of the late California-born Japanese-American sculptor, furniture designer and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. And now the public can get in on the fun by viewing scale models and sketches of playgrounds inspired by hills, dales, basic shapes and geometric patterns in the exhibition Noguchi’s Playscapes, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from July 15 through November 26.

As early as 1933, with his conceptual, unbuilt Play Mountain playground for New York City, featuring a pyramidal terrace and a carved slope on one side for children to slide down on sleds in winter, Noguchi pioneered the notion of sculpture — often organic in shape and inspired by nature — to be used and not just admired at a distance.

As early as 1933, with his conceptual, unbuilt Play Mountain playground for New York City, featuring a pyramidal terrace and a carved slope on one side for children to slide down on sleds in winter, Noguchi pioneered the notion of sculpture — often organic in shape and inspired by nature — to be used and not just admired at a distance.

Noguchi’s influence grew ever wider after his 1958 garden with Marcel Breuer for UNESCO in Paris and a years-long collaboration with architect Louis Kahn for a children’s park in New York during the 1960s. The latter park was also never built but was nevertheless an important design breakthrough.

Noguchi’s artful playgrounds, conceived as sculpted landscapes, echoed pre-Columbian burial mounds and surrealist artworks and conveyed a blend of Western and Eastern aesthetics, but they were always vested with the notion that play should never be too tightly programmed.

“Sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness,” was his lifelong mantra. It undoubtedly resonated with Bay Area artist/landscape architect Lawrence Halprin of Sea Ranch fame, who applied Noguchi’s vision in several public parks, and the late Marin-based sculptor/designer J.B. Blunk, who met Noguchi in Japan and whose monumental Brancusian redwood pieces are often shaped like landforms.

“Sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness,” was his lifelong mantra. It undoubtedly resonated with Bay Area artist/landscape architect Lawrence Halprin of Sea Ranch fame, who applied Noguchi’s vision in several public parks, and the late Marin-based sculptor/designer J.B. Blunk, who met Noguchi in Japan and whose monumental Brancusian redwood pieces are often shaped like landforms.

Included in the exhibition are also Noguchi’s stage set designs for legendary dancer Martha Graham — minimalistic, symbolic armatures that were ladder-like props for action and movement — that led him to think of equally interactive sculptural props in playgrounds. There are also photographs of built parks in Japan, where Noguchi grew up, and angular play structures in the United States, where he spent his last years and died in 1988.

Organized by Mexico City’s Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo and the Fundacíon Olga y Rufino Tamayo, A.C., in collaboration with The Noguchi Museum in New York, the exhibition was brought to San Francisco by SFMOMA architecture and design curator Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, who saw it during a visit to the Tamayo last fall.

Organized by Mexico City’s Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo and the Fundacíon Olga y Rufino Tamayo, A.C., in collaboration with The Noguchi Museum in New York, the exhibition was brought to San Francisco by SFMOMA architecture and design curator Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, who saw it during a visit to the Tamayo last fall.

The Tamayo is housed in a 1981 building that rises like a stepped mound of concrete and stone within Chapultepec Park, and it could be argued that it too is the result of Noguchi’s thinking that undoubtedly influenced the land art movements of the late 1960s. Inside and outside the museum, Fletcher saw replicas of Noguchi’s work, including his 1976 Playscape garden for Atlanta, Ga. — the only Noguchi playground that got built during his lifetime — and other ideas that could suitably be applied to Bay Area parks.

“He was really interested in the haptic [tactile] relation to art that is lost in museums. Through play, we are less socially inhibited, and as public space becomes increasingly politicized and privatized, Noguchi’s thoughtful designs for play, reflection and creative stimulation” are still the Holy Grail, Fletcher says. “Today, so many designers cite Noguchi’s outdoor works as influential.”

She knows this from personal experience. Last March, San Francisco’s 1850s ovoid, Englishstyle South Park, near her home, opened after a yearlong $3.8 million overhaul by none other than landscape architect David Fletcher, who is the curator’s husband. His new strolling garden design features oblong concrete pavers and molded vertebrae-like concrete wall benches; his firm, Fletcher Studio, in collaboration with Miracle Playsystems, also designed an inviting sculptural roller-coaster-like painted steel play structure, with netting on the sides to climb on and a row of “tire” swings suspended from its undulating frame.

She knows this from personal experience. Last March, San Francisco’s 1850s ovoid, Englishstyle South Park, near her home, opened after a yearlong $3.8 million overhaul by none other than landscape architect David Fletcher, who is the curator’s husband. His new strolling garden design features oblong concrete pavers and molded vertebrae-like concrete wall benches; his firm, Fletcher Studio, in collaboration with Miracle Playsystems, also designed an inviting sculptural roller-coaster-like painted steel play structure, with netting on the sides to climb on and a row of “tire” swings suspended from its undulating frame.

“It is definitely classic Noguchi,” the curator says, having experienced it firsthand. “We had our son’s birthday celebration there.”

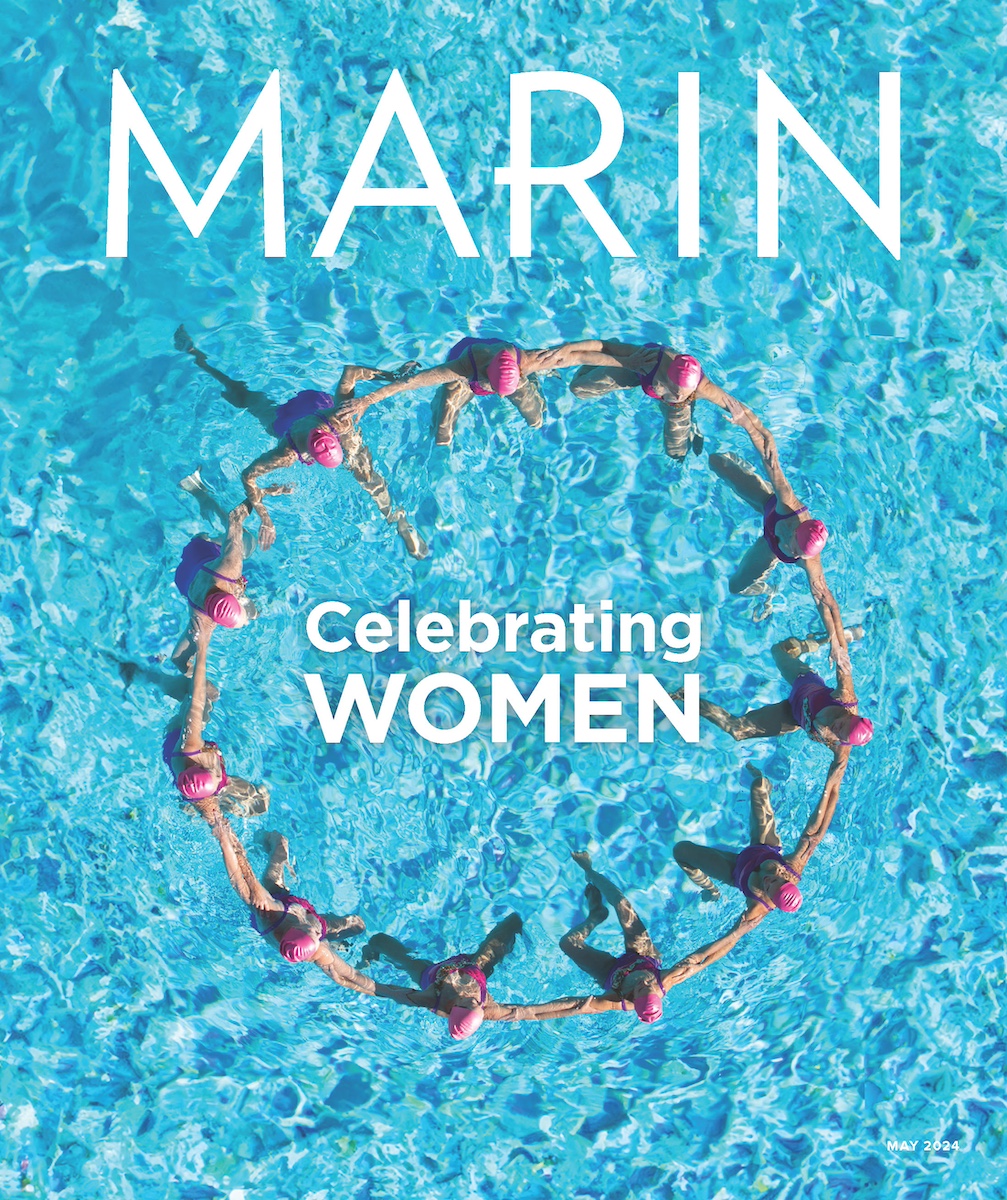

Top: Isamu Noguchi’s design for the U.S. Pavilion Expo ’70, 1968.

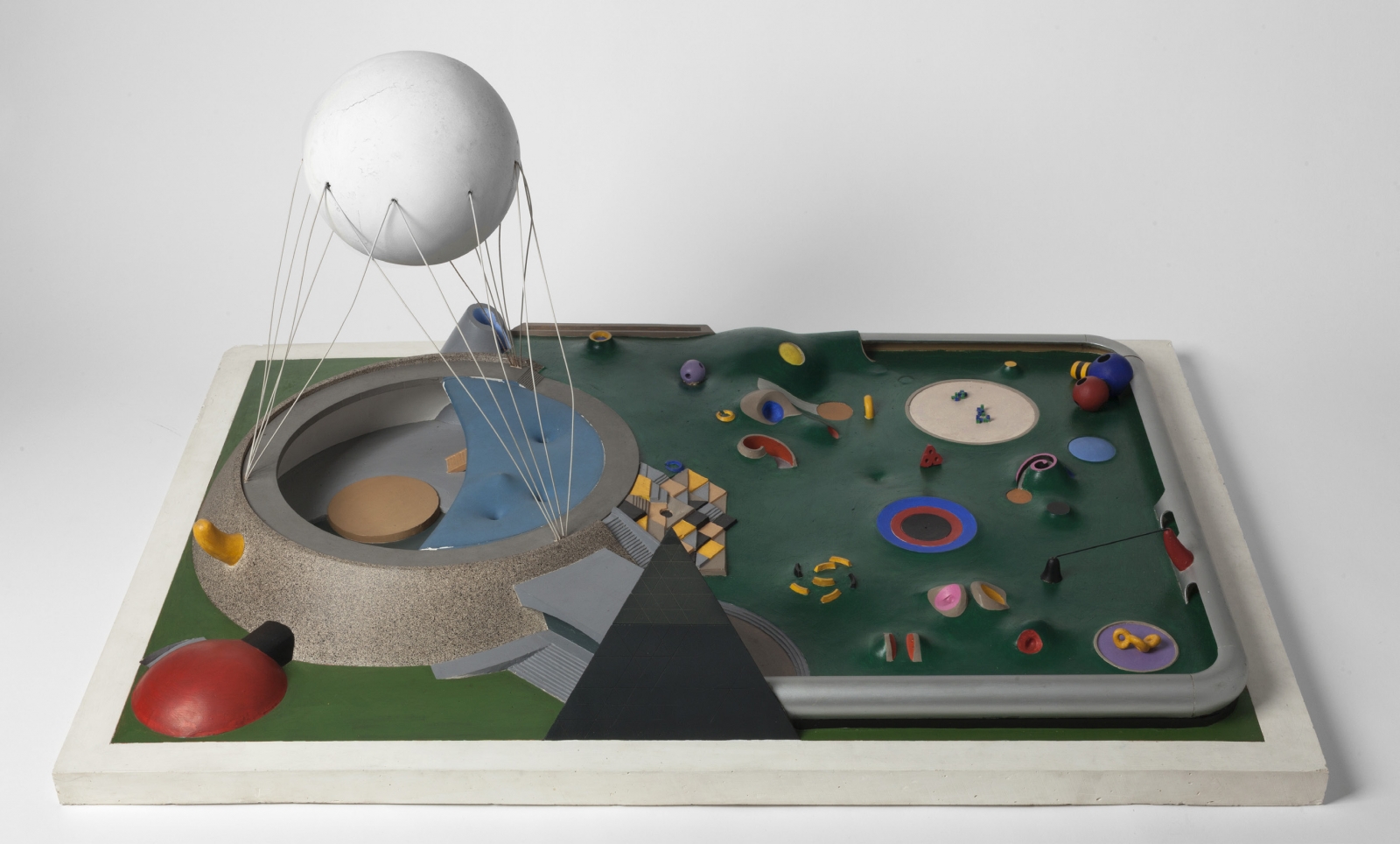

Second: Slide Mantra Maquette, c. 1985; Noguchi explored the form from 1966 until 1988 when it was eventually carved in black granite for the Odori Park in Sapporo, Japan.

Noguchi viewed play equipment that echoed forms from nature and ancient cultures as interactive art.

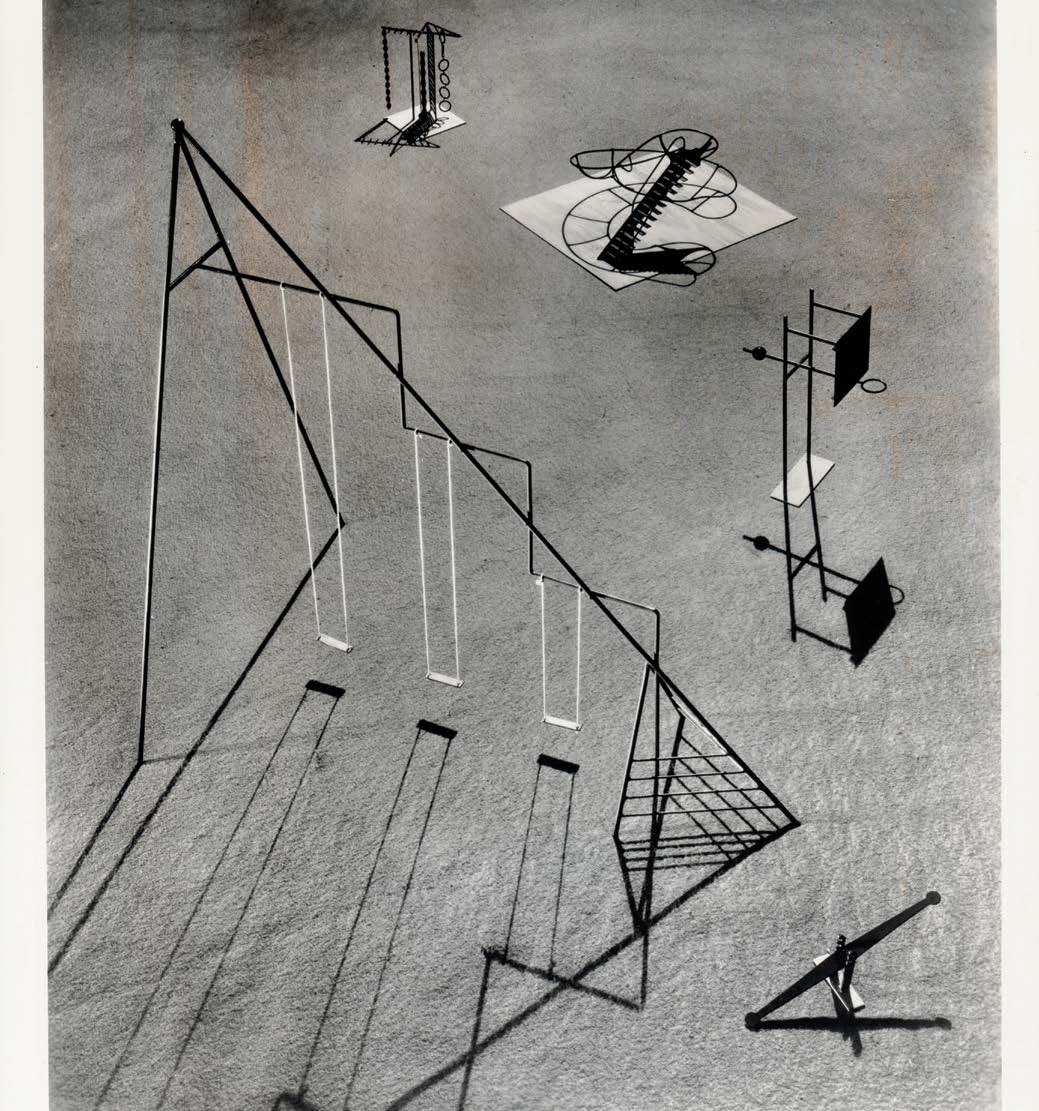

Third: Playground equipment for Ala Moana Park, Hawaii, c. 1940, is among his many unbuilt concepts;

Fourth: Photographer Fay S. Lincoln’s image of Noguchi’s playground equipment for Ala Moana Park, Hawaii, c. 1940;

Fifth: Noguchi’s Jungle Gym, a set element for performers in Erick Hawkins’s dance “Stephen Acrobat,” 1947.

Bottom: A 2017 play structure by Fletcher Studio in South Park, San Francisco.

Photos: KEVIN NOBLE © THE ISAMU NOGUCHI FOUNDATION AND GARDEN MUSEUM, NEW YORK

ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

Bottom Photo: COURTESY FLETCHER STUDIO

Zahid Sardar brings an extensive range of design interests and keen knowledge of Bay Area design culture to SPACES magazine. He is a San Francisco editor, curator and author specializing in global architecture, interiors, landscape and industrial design. His work has appeared in numerous design publications as well as the San Francisco Chronicle for which he served as an influential design editor for 22 years. Sardar serves on the San Francisco Decorator Showcase design advisory board.