Initially, the phrase “420 Louis” was a code — a reference to the time of day the Waldos would meet at a statue of chemist Louis Pasteur after school. Their agenda: to search Point Reyes for a crop of marijuana marked on a map they’d been given by a friend’s brother in the U.S. Coast Guard.

While the Waldos — Dave Reddix, Larry Schwartz, Steve Capper, Mark Gravitch and Jeffrey Noel — never found their bounty of bud, the term “420” stuck. It became an easy way to refer to marijuana without parents or teachers being the wiser, which was fantastic for the group, as smoking pot was part of nearly everything they did.

Now, almost 50 years later, Reddix and Capper are still marveling at the way their little inside joke has spread around the globe. Seated in Capper’s Sleepy Hollow home, they review the latest traces of their unexpected legacy. For starters, there’s H.R. 420 — a bill recently introduced in Congress by Rep. Earl Blumenauer of Oregon. Officially known as the “Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol Act,” the legislation seeks to build on a mounting public outcry calling for cannabis to be removed from the federal Controlled Substances Act. Capper and Reddix believe that step could help many unjustly incarcerated individuals go free, but they acknowledge such efforts remain controversial within the larger cannabis community. “We’re not political,” Capper says. “We’re not one side or the other.”

Another recent 420 reference comes courtesy of Tesla founder Elon Musk. “It was funny to watch him get in trouble for saying that the stock price would be evaluated at $420 a share,” Capper says. “He did it to impress his girlfriend, who likes to smoke out, and then all of a sudden he was in trouble with the [Securities and Exchange Commission].”

Musk’s misstep isn’t the biggest instance of 420 entering the zeitgeist. That would be the unofficial adoption of April 20 as a high holiday for marijuana worldwide. In San Francisco, thousands gather on this date each year at Golden Gate Park’s “Hippie Hill” to light up in unison when the clock strikes 4:20 p.m. Similar celebrations large and small happen everywhere from Vancouver to Amsterdam.

No one in the group is entirely sure just how the number leapfrogged their circle to become something so massive. Reddix notes that his brother Patrick Reddix was close friends with Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh, even managing two of the musician’s side bands, which almost certainly helped: in 1990, a flier for a Dead show in Oakland made ample use of the term and found its way to the offices of High Times, which published the first article investigating the origins of the phrase.

Capper first realized just how big 420 was getting when fellow Waldo Larry Schwartz phoned him in 1997. “Larry called me up one day. He said, ‘Steve, it’s everywhere. There are T-shirts and hats. Everybody is capitalizing on it.’ ”

Reddix recalls hiking with Capper in the expanses of Utah and finding a tree with 420 carved into its trunk. For a time, 420 inspired a real-life Waldo Easter egg hunt: whenever one of the gang saw a graffiti tag or park bench engraving, they’d gleefully share the news.

In 1998, the Waldos contacted High Times in hopes of setting the record straight, so to speak.

Their evidence was compelling. Among the keepsakes (currently stored in a bank vault) they offered as proof of provenance was a postmarked letter from Reddix to Capper mentioning 420 in the early 1970s. There’s also a 420 flag a friend of the Waldos made for them in arts-and-crafts class at San Rafael High.

Reddix says the Waldos have little interest in benefiting financially as 420’s creators; they just want proper credit. Besides, while the number’s improbable popularity has been a wild ride, it’s only one of countless signifiers of the gang’s mischievous days. “It’s totally secondary,” he says. “When Most noteworthy is the unofficial adoption of April 20 as a high holiday for marijuana. Marin County has never suffered from a lack of celebrity residents. Over the years figures like Metallica’s James Hetfield, actor Robin Williams, and novelist Isabel Allende have all lived here. Yet in addition to the writers, musicians and film stars, Marin has been home to another set of famous folks. They haven’t starred in movies or written hit singles, but the five friends known as the Waldos have become counterculture phenoms, thanks to a slang term they invented as students at San Rafael High School in 1971. you think about it, we didn’t get any coverage on this until 1998. That was 27 years after we created the term. That’s a long time.”

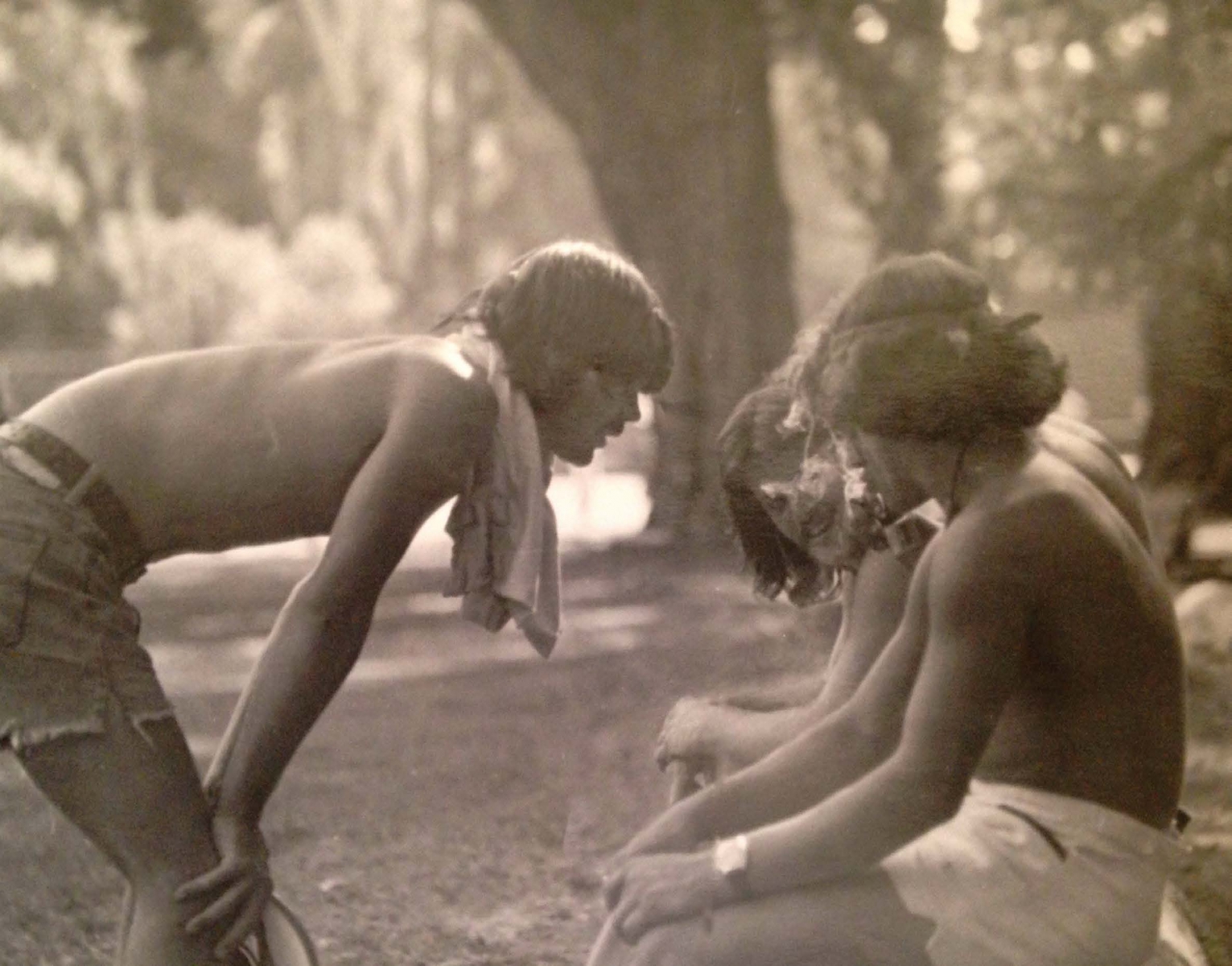

On the right: Waldo Mark (front), Waldo Larry (middle) and Waldo Dave (back) share a joint with a non-Waldo (left) at Dominican University in San Rafael after playing Frisbee golf.

So what were the Waldos doing when not hunting reefer in Point Reyes? Most of the time, riding around in Capper’s 1966 Chevy Impala on “safaris” — impromptu escapades that more often than not involved smoking a little grass and doing something slightly insane.

“We went to all kinds of places in Marin,” Capper says. “We’d go to the Golden Gate Bridge, get high, and jump in the painters’ nets.” “We’d climb out on the girders,” Reddix explains. “Underneath there was a net in case someone was painting and they fell off. We’d go out there, get stoned, and start jumping in those nets like they were trampolines.”

Other antics: driving to Hamilton Army Airfield in Novato to sprint across the runway as planes were taking off; racing the planes in Capper’s Impala; surprising unsuspecting elevator riders by stopping the lift between floors and pulling apart the doors. After reading in Rolling Stone about a laboratory working with holograms near Palo Alto, Capper decided to visit it in the middle of the night. “I got fed up with a football game, so I went down there. It was like one in the morning; I pounded on the door and asked if I could see the holograms. They said, ‘Yeah! Come on in! We’d love to show you!’ ”

“Basically, we were a brotherhood of outlaw weed smokers,” Reddix says. “We’d challenge each other every week to come up with a new, weird place to go.”

These days, 420 pops up in the Waldos’ lives in other kinds of surprising ways. Last December, Reddix’s brother Pat passed away after a battle with cancer, and beyond family, longtime friend Phil Lesh was also there during that difficult time.

“I was there, and Pat died at exactly 4:20 p.m.,” Reddix says. “It’s on his death certificate. What are the chances of that?”

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s print edition with the headline: “High Times”.