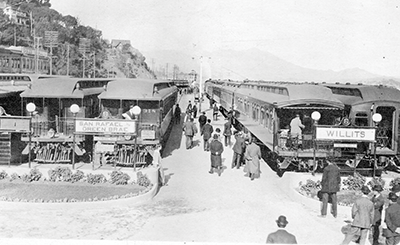

IT’S 1916, YOU’RE living in San Rafael and the weekend is coming up. What are you going to do? Here’s one idea: the Northwestern Pacific Railroad recently completed a line that goes north to Ukiah, Willits or Eureka. Why not take it and stay somewhere overnight? Or maybe head over to Mill Valley and ride the World’s Crookedest Railroad up to the top of Mount Tamalpais, meeting friends at the West Point Inn? Or take an interurban electric from the nearby B Street station down to Sausalito, then catch a ferry to San Francisco and watch soldiers parade down Market Street before they head off to World War I? There are lots of choices. And in Marin, in 1916, many of them involved traveling by train.

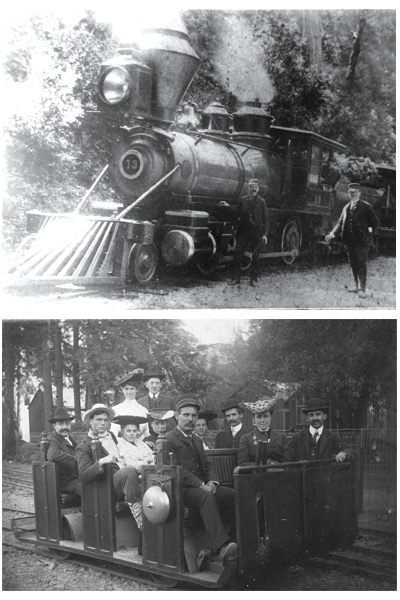

Historians say the 55 years from 1875 to 1930 were Marin’s great era of rail. Steam-powered engines departed from Tiburon and Sausalito for Eureka, 284 miles away. And by 1896, sturdy steam engines were pushing open-air cars, filled with tourists from all over the world, through 281 curves and over eight miles before reaching the summit of Mount Tam, then coasting down into Muir Woods. In 1903, many rail lines were electrified, and Marin pioneered the concept of an interurban commuter electric rail system connecting (and helping to develop) Marin’s cities and towns.

So where did it all go? What still remains of those freewheeling railroad times in today’s traffic-clogged Marin County? Where are the reminders? A look at Marin’s three rail systems reveals some answers.

Steam-Powered Rail System

Starting in early 1869, Marin’s first railway ran about three miles between Point San Quentin and San Rafael. But by the mid-1880s, the primary terminals for steam-powered trains were Tiburon and Sausalito, because these were port cities where ferries could then take freight and passengers on to San Francisco. All rail lines originating in Marin then headed north, either to Cazadero in coastal Sonoma County or to Eureka, pretty much following the course of the present-day Highway 101.

Today, a prominent remnant of that era is the Donahue Building, built in 1884 by rail pioneer Peter Donahue and still standing in Tiburon’s Shoreline Park on Paradise Drive. This two-story gray structure was faithfully restored by the Belvedere- Tiburon Landmarks Society in 1985 and now houses the Railroad and Ferry Depot Museum. Downstairs is a model train layout of Tiburon as a railroad town; upstairs is an authentic 1900s depiction of the stationmaster’s living quarters. According to Phil Cassou, managing docent of the museum, “the last freight train left Tiburon on September 25, 1967.”

The route that train traveled out of Tiburon is now a popular bayfront walking and biking path aptly named Old Rail Trail. Once that route turns inland, heading toward San Rafael, the only remains of what was once a 775-foot wooden trestle and an earthen berm, built in 1884 to span a marsh, are a few weathered beams and a 600-foot berm overlooking Blackie’s Pasture and Tiburon Boulevard. Efforts are being made to reconstruct 40 feet of that old line, along with a 600-foot Trestle Trail atop the berm, to honor the area’s railroad history. The only other remnants of the line that by 1916 reached Eureka are the Cal Park Tunnel (south of San Rafael) and the Puerto Suello Tunnel (in north San Rafael); both are more than 1,100 feet long and have recently reopened to accommodate the soon-to-arrive SMART commuter trains.

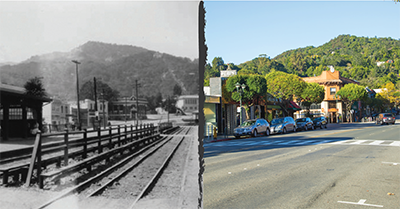

While Sausalito was the terminus of an 1875-era steam train line to the coast of southern Sonoma County via Point Reyes Station — and was handling both steam and electric freight and passenger lines by 1903 — the only present-day evidence of its railway past is, again, a biking and walking trail. This one connects Bridgeway in Sausalito to East Blithedale in Mill Valley. Mill Valley, San Rafael and Point Reyes Station all had stations handling passengers and freight traveling by steam-powered trains during Marin’s prime railroading days. However, due to various alterations, only Mill Valley’s depot remains recognizable as a train station today — and it functions as a bookstore, cafe and chamber of commerce headquarters.

Get SMART

Rediscovering the richest remnant of all.

“It was sometime in the early 2000s,” recalls Dietrich Stroeh, a Marin civic leader who’s been active in community affairs since the 1960s. “I was on the board of the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District and we had this Northwestern Pacific Railroad right-of-way that was not being used.” As Stroeh was talking with fellow board member and former mayor of San Rafael Al Boro, “suddenly I asked, ‘Why not build a new railroad on it?’ ” With that, SMART, Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit, was born. When considering what kind of a “footprint” Marin’s railroading history has left on the present day, the right-of-way SMART was in essence given has to top the list. If all goes well, in spring 2017, seven two-car commuter trains will start running between downtown San Rafael and the Santa Rosa Airport, 43 miles away, with hopes that they will reduce vehicle traffic. SMART’s cars, self-powered with Cummins QSK19-R diesel engines that meet the EPA’s rigid Tier 4 guidelines, will travel a route identical to that once taken by steam locomotives. Basically, they’ll head out of San Rafael, pass through the Puerto Suello Tunnel, then make many of the same stops — Novato, Petaluma, Cotati, Santa Rosa — that the NWP did more than 100 years ago. Only the tracks and the rail bed have been changed. So when you read that SMART — the “largest public works project in the history of either Marin or Sonoma counties,” according to general manager Farhad Mansourian — will cost an estimated $450 million, consider what the cost would have been without the benefit of a right-of-way no one knew what to do with. “It would have been astronomical,” says railroad historian Fred Codoni. “Just think of acquiring a 25- to 50-foot strip of land that goes for 43 miles or more at today’s prices — thank God they saved it.”

The Mount Tamalpais Scenic Railway

Prior to the automobile and the Golden Gate Bridge, there was the Mount Tamalpais Scenic Railway. Starting in 1896, it snaked from Mill Valley 8.2 miles to the 2,571-foot-high pinnacle of Mount Tam. Its steam locomotives faced backward and pushed, not pulled, open-air cars up the mountain. That way its cars couldn’t break loose and hurtle down the tracks; smoke and soot would not engulf its wellcoiffed passengers; and the trains didn’t have to turn around before heading back to Mill Valley.

In 1902, so-called Gravity Cars were added to liven up this popular tourist attraction. These were powerless four-wheeled vehicles that carried up to 30 passengers and would careen down the rails, propelled only by gravity, at up to 25 miles per hour around some corners (by company edict the limit was 12 mph and employees were fired for exceeding it), controlled only by a brakeman who had a front-row seat. Then, in 1907, halfway up the mountainside a line was added that ran two miles down into neighboring Muir Woods, the 612-acre grove of redwoods soon deeded to the U.S. park service by Marin Congressman William Kent.

Despite the attraction, the Mount Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railroad ceased operating in 1930. Its demise, most rail historians agree, was the 1925 completion of a dirt road — later to be paved and named Ridgecrest Boulevard — to Mount Tam’s summit. “Over the years, for some silly reason,” laments Fairfax’s Fred Codoni, “people liked driving up, instead of riding up.” Also, in 1929 a devastating forest fire on Mount Tam destroyed one of the line’s engines and much of its infrastructure. Late in 1930, with the onset of the Great Depression, all of the track from the World’s Crookedest Railroad was removed. According to Fred Runner, author of Mount Tamalpais Scenic Railroad, “it took one engine and 20 men to do the job in about two months.”

Yet even there remnants remain. “A case can be made that Old Railroad Grade is the most important (trail) on Mount Tamalpais,” writes Barry Spitz in Tamalpais Trails. That nearly seven-mile route to the top follows almost exactly the gradual grade (never more than 7 percent) that the railroad took to and from the Mill Valley station. The wide and fairly smooth path is popular with hikers and mountain bikers. Not quite halfway to the top, in an area known as Double Bow Knot, a long and cracked concrete curb is the only surviving trace of Mesa Station, where gravity cars once took off for Muir Woods.

A much bigger relic is West Point Inn, built in 1904 and still very much alive as a spot for hikers and bikers to rest and refresh while on Mount Tamalpais. At the top itself, about all that endures from the railway days are portions of the cement-and-stone foundation of Tamalpais Tavern, a glamorous dining, dancing and gathering spot that burned down in 1923. However, a recently constructed Gravity Car Barn (open Saturday and Sunday, noon to 4 p.m.) holds a replica gravity car, 98 feet of track, and provocative exhibits, including a rare video of the cars in action and interviews featuring the folks who dared to ride in them.

Interurban Electric Rail System

It was 1903 when most rail lines within Marin were converted to handle an interurban electric rail system. Along with New York City, Marin was among the first areas in the U.S. to operate such a network. It consisted of self-propelled cars that were more cost-efficient to operate, fumeless and powered by a notorious (and dangerous) third rail that was added to existing tracks and carried 600 volts of electricity. The cars connected all of Marin’s municipalities except Tiburon and Novato; their nexus was the still-busy San Anselmo intersection known then and now as the Hub.

Today, some people insist that the electric rail vehicles of years ago, in conjunction with ferries out of Sausalito, were more efficient in moving commuters than today’s buses and ferries. At the time, people feared interurban electrics would lead to a surge in development in Marin. That didn’t happen. “At its best, the system only collected 20,000 fares, representing 10,000 people, in a single day,” writes Harre Demoro in Electric Railway Pioneer. The county’s population never exceeded 45,000 during the interurbans’ days of operation, and in May 1937, the Golden Gate Bridge opened and people began driving their cars into the city. Marin’s last interurban electric cars ran on February 28, 1941.

The electrics also left plenty of traces. The aforementioned multipurpose pathway between Sausalito and Mill Valley was a popular interurban electric route. After reaching East Blithedale, the cars would head toward Corte Madera by way of the Alto Tunnel, a 2,200-foot-long bore that is currently in disrepair, although concerted efforts are underway to reopen it as a biking and walking path.

From Corte Madera, the old electric line heads straight into Larkspur by way of Baltimore Park, an area that’s a treasure trove of rail relics. Drive out Alexander Avenue and you’ll cross the Holcomb (or Alexander) Bridge, built in 1922 to allow trains to pass beneath its distinctive arched concrete superstructure (there are only six like it in California). Now it sees mostly school kids and seniors passing underneath on a wide and smooth pathway. Take a few steps north and you’ll see a concrete foundation that once anchored the interurban electrics control tower No. 3. Glancing to your right, you’ll see a massive concrete-and-brick structure labeled “Baltimore Park Substation.” It was an integral part of Marin’s interurban electric train system. Evidently it was too imposing to consider tearing down.

And some vestiges of Marin’s vast train system are hiding in plain sight. Continue into downtown Larkspur and check out that tile-roofed low-slung building east of Magnolia Avenue across from the Lark Theater. It’s now King of Roll, a Japanese restaurant owned by a gentleman of Chinese descent who goes by the name John Wayne. Once upon a time, that was the Larkspur train station. Finally, remember how earlier we harked back to 1916 and rail’s heyday in San Rafael? Sometime after the last running of the electric interurbans in 1941, someone managed to move the Mission-style station building from B Street (where the tracks were) over to A Street, just south of Second. It’s now known as Tino’s Hair Studio, it still displays Northwestern Pacific Railroad plaques, and it’s a great place for a $20 haircut.

Historians Phil Cassou, Fred Codoni, Fred Runner and Richard Torney contributed to this article.