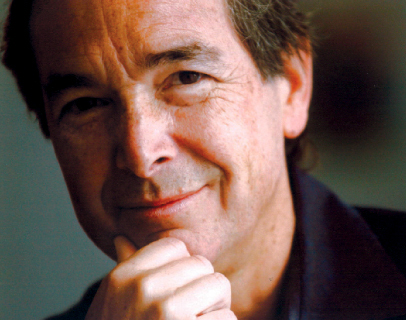

Martin Cruz Smith is not a Russia expert. Which is strange, considering that his series of Arkady Renko detective novels sure make him seem like one. In them he traverses the geography, language, culture and history of Russia with the ease of a native. But the San Rafael resident doesn’t even speak Russian.

“If left on my own in Moscow I am bound to get lost,” he says. Of course, this can be a good thing. “When I do get lost, it doesn’t matter—it’s all material, all stuff I didn’t expect.” Smith, who goes by Bill (his real name is Martin William Smith, but when he began publishing there was another writer by that name, so he added Cruz, his grandmother’s name, to distinguish himself), has written more than 25 novels, sometimes under the pen name Simon Quinn, Nick Carter or Jake Logan, but he is best known for the six novels starring Arkady Renko, a cynical Moscow police detective whose ethics and sense of justice make him a pariah in the department. Renko first appeared in the 1981 novel Gorky Park, which won Smith the Golden Dagger Award and was called “the thriller of the ’80s” by Time magazine.

Twenty-six years later Russia has changed a lot and, much to Smith’s surprise, he and Renko have changed right along with it. “[After Gorky Park] I was determined not to write a sequel,” he says. “I had done my Russia book, I thought. But then Russia started to change and I wanted to get back in.” Easier said than done. After the publication of Gorky Park, which was distributed illegally in the Soviet Union, Smith was banned from the country. It became a crime to even own a copy of the novel.

To research his next book, he found a way around that by spending time on an American trawler that delivered fish to a Soviet ship in the Bering Sea. That way he was exposed to part of Russia without actually setting foot on its soil. By the time the KGB caught wind of his whereabouts, he had enough material for what became the second book, Polar Star.

Luckily for him, Smith has chosen a subject and setting that continue to yield rich material for fiction: massive political change, organized crime, corruption, nuclear accidents, an ongoing war and a deep sense of nostalgia that seems to permeate all things Russian.

His new Renko novel, Stalin’s Ghost, was born of the country’s continuing transformation. “Things are changing back,” he says. “That was the whole point of Stalin’s Ghost. A man who sent millions to their deaths has now become a figure of adulation. This doesn’t happen without the consent of the government. Bit by bit he’s rising from the grave.”

The novel begins with late-night subway passengers reporting sightings of Josef Stalin’s ghost on the station platform. Set against the fallout from the Chechen conflict and the culture of corruption in Moscow, the story has murder at its center, but it’s not a simple whodunit. Instead of the genre’s usual red herrings and plot twists, it closely follows Renko who, fueled by personal jealousy and a sense of decency, carefully builds his case against fellow police officers suspected of killing for hire. The story manages to combine an up-till-dawn pace with a literary thoughtfulness to provide an eye-opening portrait of contemporary Russia.

And happily for Smith’s legions of fans—many of them in Russia, where his novels are for sale at every street kiosk—it’s not the end of the Renko story. “I am working on another Russia book,” he says. “Democracy as we know it is already over in Russia. It’s very much managed by Putin and his handpicked successor.”

And happily for Smith’s legions of fans—many of them in Russia, where his novels are for sale at every street kiosk—it’s not the end of the Renko story. “I am working on another Russia book,” he says. “Democracy as we know it is already over in Russia. It’s very much managed by Putin and his handpicked successor.”

This unfortunate state of affairs is likewise rich with fictive potential, especially in the hands of an author who clearly loves to pit the little guys against the big ones. “I am attracted to the form of the detective story,” Smith says, “because in any society there are questions that are not asked except when there is a crime involved and then people have to answer them for themselves. It’s an intersection where high and low, rich and poor meet, where the lord has to speak to the lowly policeman.”